Friday FTW: China’s Human Rights Violations Enjoy a Moment in the Spotlight

Vincent Colistro

When I returned from China over the summer, having worked there for a year and a half, people would ask me, “What was it like?” And I, like a child trying to verbalize their first lofty idea, was sort of tongue-tied. There are over a billion individual perspectives in the country, yet only one autocratic organization at its helm. It is barely reined in chaos. It’s wild yet it’s orderly. It’s filled with earnest workers and disingenuous ladder-climbers. It’s pro-gay and anti-gay. It inspires close scrutiny yet offers little in the way of answers.

One thing we can say with authority is that its government doesn’t have the finest track record for human rights—detaining activists, suppressing protest, heavily censoring the Internet, and just generally eschewing democratic processes. We’re talking about the rights of roughly one-sixth of all humans. That’s why, when the UN’s Human Rights Council opened up its first investigation of China since Xi Jinping became president, I expected the government to get a good public shaming.

I was … sort of satisfied. Some countries actually trumpeted China’s progress and human right’s accomplishments—Russia said, “We commend China on protection of rights of religious beliefs”, and Yemen applauded “China’s remarkable achievements in economic and social achievements [sic]”. Most Western countries, however, reproached China for the aforementioned issues (as well as its draconian capital punishment policies and stance towards ethnic minorities). Canada, among the most direct, said, “Stop the prosecution and persecution of people for the practice of their religion or belief including Catholics, other Christians, Tibetans, Uyghurs and Falun Gong… And eliminate extrajudicial measures like forced disappearances”.

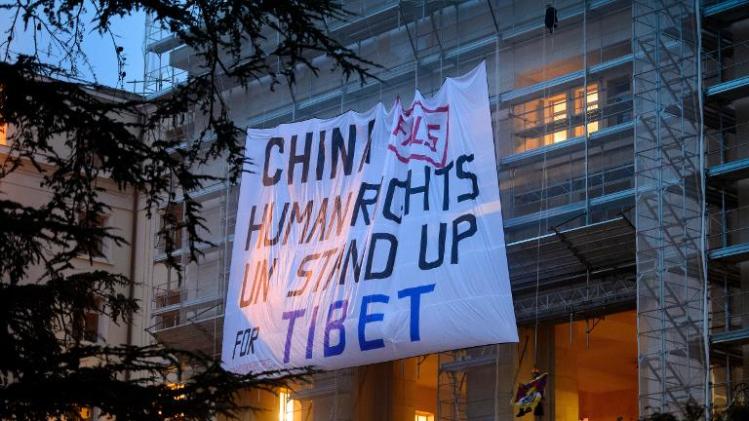

But the real win this week goes to the Tibet activists who scaled the height of the UN’s Palais de Nations to unfurl a large 9X15-meter banner reading: “China fails human rights in Tibet—U.N. stand up for Tibet”. The banner was in response to China’s colonization of Tibet (China calls it a “peaceful liberation”) and their assimilative policies, which have led some, including the Dalai Lama, to use the term “cultural genocide”. Since 2009, there have been at least 122 self-immolations in Tibet in response to China’s unwanted presence. It’s good to see the issue continue to garner attention in the west, aside from those ubiquitous bumper stickers. As for the four activists responsible, they can’t be arrested, but they’re being sent back to their home countries (Denmark, UK) to be dealt with locally.

Sadly, we aren’t able to hear what the average Chinese citizen has to say about the human rights issue in China, as netizens are fiercely censored surrounding such topics. When I was teaching there, I polled my class of 25 16-year-olds on whether they thought homosexuality should be allowed in China, and all but two of them agreed that people should be able to love whomever they want. When I asked them about Tibet, however, they didn’t even know that it was an issue outside of China. These are, of course, anecdotes, but I use them to illustrate that there is a difference between Chinese citizens and the Chinese government, and if the people were only given access to more information, the world’s most populous country could really be a force for good. For now, we can take small solace in knowing that those who’re being persecuted and marginalized have a voice outside of China—it’s not ideal, but it’s a start.